I caught Cottonmouth at this year’s Round Top Film Festival, and it left me both unsettled and impressed—a gritty Western thriller that doesn’t pull its punches. Directed by Brock Harris, the film is steeped in dust, betrayal, and retribution, a modern take on the old frontier morality tale. It’s not an easy watch—bleak, violent, and at times painfully grim—but there’s a strange magnetism to it that kept me engaged from the opening vows to the final reckoning.

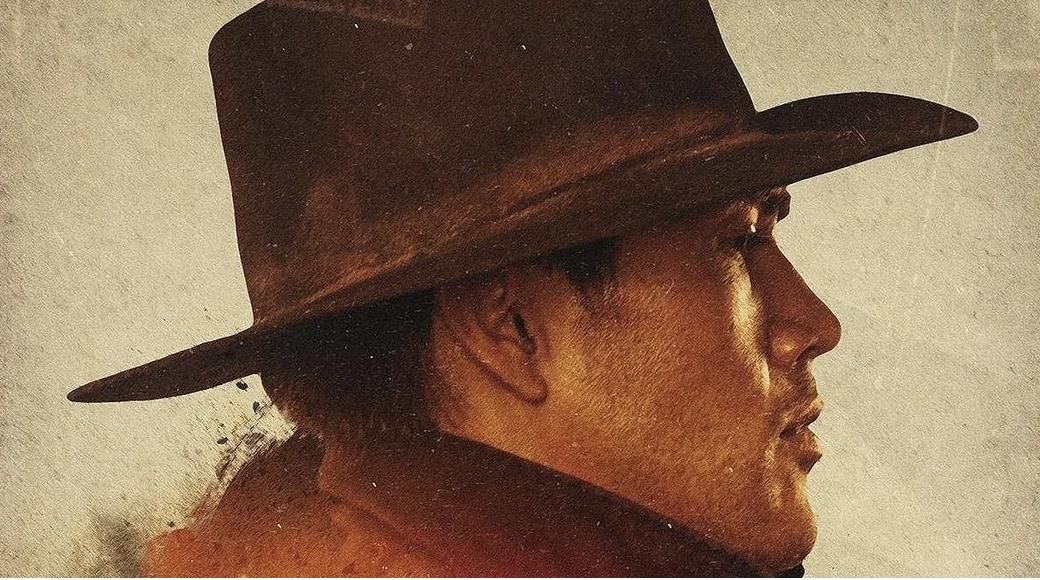

Martin Sensmeier plays Ed Dantes, a cowboy whose wedding day becomes a nightmare when his best man betrays him and frames him for multiple crimes. The story quickly shifts from romance to horror as Dantes is sold to a sadistic warden who carries out brutal experiments on inmates at a lonely territorial prison. Sensmeier brings quiet dignity to the role, his performance simmering with anger and disbelief. It’s a role that demands both physical endurance and emotional control, and he convincingly delivers both.

The supporting cast—Jonathan Sadowski, Eric Nelsen, Alyssa Wapanatâhk, James Landry Hébert, Ron Perlman as Warden Victor Cain, and Esai Morales as Abe—brings horror, grit, and humanity to a story that might otherwise feel too dark to endure. Wapanatâhk in particular provides the film with a pulse of compassion, grounding the violence with a touch of warmth and a stunning singing voice.

Visually, Cottonmouth is striking. The camera captures a frontier that feels both mythical and claustrophobic—wide horizons that somehow offer no way out. Harris directs with confidence, using silence and shadow as effectively as gunfire. Still, there’s no denying the brutality on screen. The violence is sometimes hard to watch, not because it’s gratuitous, but because it’s relentless. The prison scenes are especially intense, and there were moments I found myself tensing up in my seat.

If the film has a flaw, it’s predictability. The betrayal, the revenge arc, the grim catharsis—they unfold in recognizable ways. Yet even as I guessed where it was headed, I couldn’t look away. The pacing and performances add depth, and the craftsmanship raises what could have been a standard Western into something with real atmosphere.

By the end, Cottonmouth felt less like a genre exercise and more like a fever dream of guilt and survival. It’s not for everyone—its darkness lingers—but for those who can handle its violence, it’s an impressive, unflinching piece of work. Watching it in Round Top’s hushed, beautiful Festival Hall, I found myself both shaken and appreciative. Cottonmouth may not offer comfort, but it certainly commands attention.